24 November

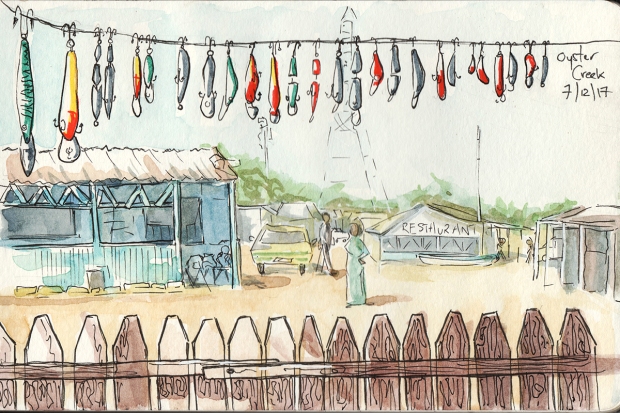

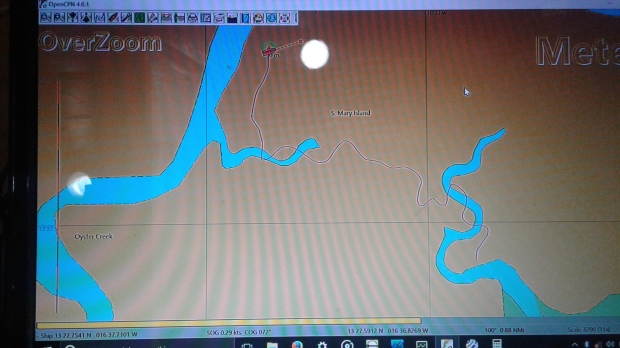

This morning we woke at the furthest point we’ll reach up the river Gambia. We drank a coffee, ate bread and eggs and started the engine to head back to Banjul. To write about our trip, particularly while it’s still underway, is quite a challenge – it feels as though every day has been some auspicious first, each event the highlight or lowpoint, each encounter somehow significant. I know I’ll forget to mention animals, birds, insects and people we’ve seen. I guess I’ll just start where I left you, at Oyster Creek, and try to piece it all together as I go.

We stayed there for a couple more days, allowing Rich to purchase some fantastic trousers, Abraham to get a new tube welded on to our anchor windlass handle and me to develop an addiction to the bread and beans that are sold from pots at the sides of streets for breakfast. We walked one morning down Old Cape Road, a long street with little to either side except beautiful marshes and birdlife until it opens up to a craft market. From there we were able to wander Bakau’s dirt roads and side streets to find the pool of friendly crocodiles at Kachikally, the botanical gardens where we got bitten to pieces by bugs as we relaxed on a bench and the vegetable market where we restocked our supplies for our impending trip up river. All over the area and nearby Serekunda graffiti expresses the excitement of Gambia’s recent liberation from dictatorship: “#Gambia Has Decided”

It was while we were admiring the pirogues of the fishing beach in Bakau that Rich and I fell foul of some absolute arseholes. We had politely shrugged off plenty of other tourist predators earlier in the day, but theirs was a more sophisticated scam involving several characters: a couple of smiling gents on the foreshore who wanted to show us round their fishing area followed by a younger man, supposedly of some standing in the community, who they (without our knowledge) had fed details about us, and a further supporting cast of women and children back in their domestic base. Once we had enjoyed a pleasant tour of the fishing processes we were persuaded to visit this base and, once surrounded there, to part with money for supposedly orphaned children, and then even to lend a little money for a minute for one host to go to a shop, after which a “fight” broke out between two of them and we were rushed to leave. Though the cost to our prides was much higher than that to our pockets (fortunately we did not have much money to give, otherwise they might have persuaded us to “donate” and “lend” more) we would continue to think on the occasion with a shudder over the next couple of days, exclaiming to each other after thoughtful silent pauses about the skill with which they had manipulated our fear of offence and desire to respect custom, our generosity, trust, naivite and vanity. We resolved not to let it dampen our desire to engage, and not to let it happen again.

Vulture, hornbill and friends on Old Cape Road

These smily bastards are fed frequently so apparently don’t want to eat you.

Monitor lizard among the crocs

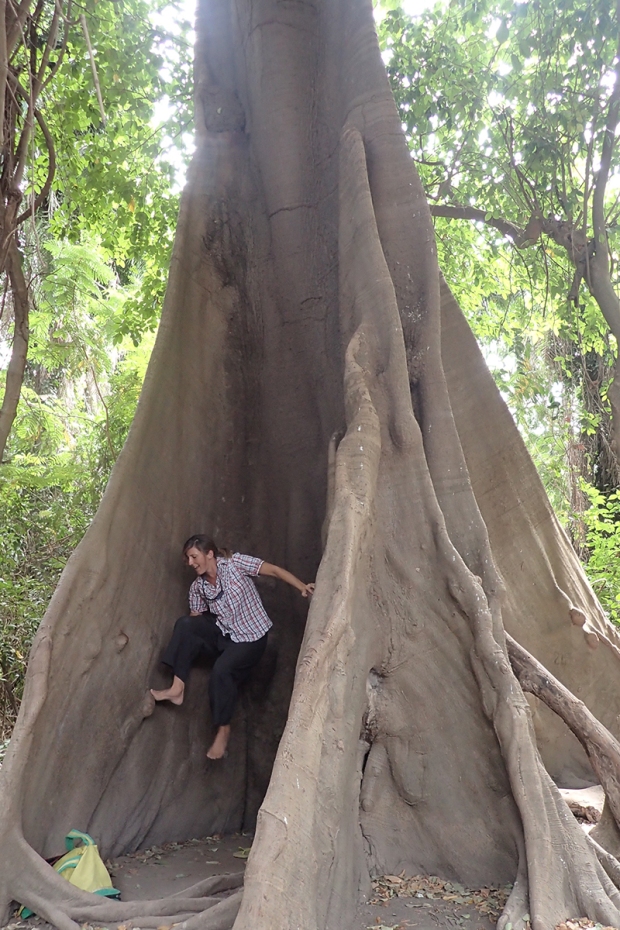

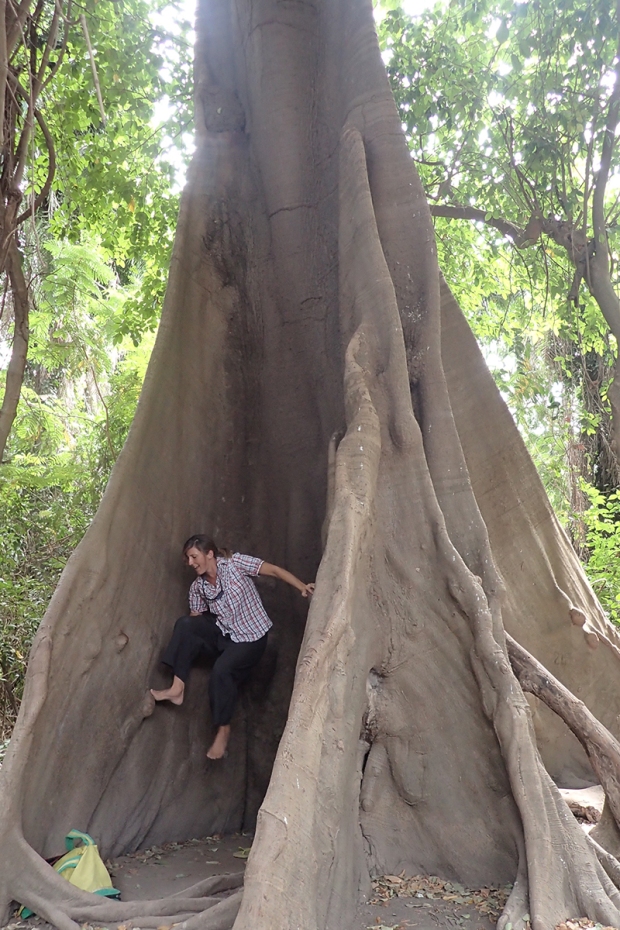

Buttress. Well, that’s one term for me.

Mate, there’s a crocodile in your trough.

Bakau botanical gardens. Beautiful but painful on the ankles.

The beach of swindles

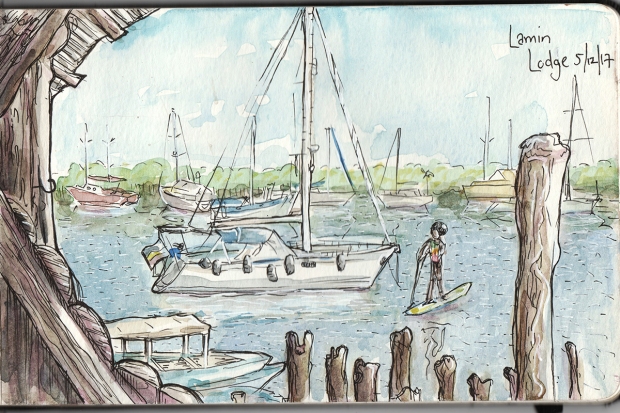

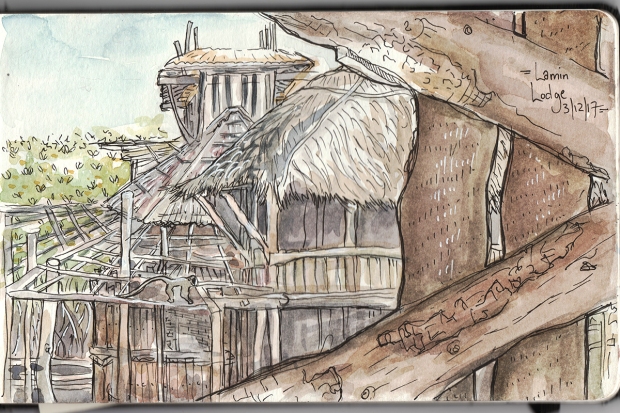

It was a relief to detach ourselves from the world of people as we began our journey up the Gambia the next morning. We had only intended to take Gwen as far as Lamin Lodge, the other anchorage noted in our twenty year old pilot guide, but spurred on by a favourable wind and tide we decided to start the larger journey a day or two early. We motored out of the mangrove creeks and sailed a long relaxed route across the river mouth until the wind came too much against us and the engine was started again. Over those first salty days, as we left the sea behind, various pods of bottle nosed dolphins came to investigate and swim alongside and around us. The dirty freshwater of the river rolled and bumped with salt water in swirling clouds of brown.

That afternoon we arrived at what our charts call James Island, now renamed Kunta Kinteh Island after the locally celebrated protagonist of the book, TV show and film “Roots”, and met one of its guardians who was seeing off the last tourist boat of the day. He sold us a ticket and told us some of the history of the place before disappearing, leaving us a small land and ruined castle of our own. It’s always shocking to be faced with a relic of slavery, and though the slave quarters themselves have long been lost to the river it felt a strange place to be having a romantic evening picnic. The shores were spattered with long thin spiral shells on sand and mangrove roots in mud, clinging to stumpy supporting walls that have been added to stop the whole island washing away.

River dolphins in the river, dolphining

Bowsprit selfie

You don’t get this in the Tamar

Crumbling castle on Kunta Kinteh

There were heaps of these, so I don’t feel too guilty about how many I ran away with

Jetty Setty

One well preserved cannon…

…and another that had been colonised by mangrove oysters.

Our home for the night

We would not sail again on our upstream journey – the wind tends to come down the river, if it comes at all. The next morning we began a pattern that has endured: rest or explore by dinghy when the tide is against us, press on when it’s with us in daylight. We motored, keeping the revs low to avoid overheating the engine in the warm water and staying central to keep our depth. The only other inhabitants of the wide river were dolphins and fishermen. Unlike those we’d seen at sea, river fishing canoes are usually dug out from a single trunk with boards attached for repairs, controlled with heart shaped paddles on long sticks or outboard motors, and the fishermen in them drop or gather long nets that we often have to steer to avoid. They almost always wave to us, and we’ve been lucky enough to buy fish for dinner from a couple of them along the way.

A snaking line of flamingos flew against a distant backdrop of the new mangroves, taller than those around Banjul, which would line most of the rest of our journey. We turned off to anchor half an hour’s potter up Mandori Bolon which, like all the creeks we have encountered, was fine to navigate once Gwen was past the scarily shallow entrance. Here stone curlews, hammerkop, huge eagles and vibrant kingfishers in a range of colour and size joined the pigeons, egrets, pelicans and herons that we were getting used to. As soon as we were happy with the boat’s turn in the current we jumped in Fanny to explore the stream that is their home. We’d neglected to take shoes and so were reluctant to go ashore in the sharp sticks of the mangrove base, but once we reached a field of muddy vegetation the temptation was too great and we waded in with a sucking, squishing stomp, examining footprints that were not our own with curiosity – otter? crocodile? We were about to head home when Rich saw a few dark shapes in the distance. He called me over to look through the binoculars “Mammals!” but it was hard to see: they raised their heads and shoulders like people but were on all fours, and then one ran across incredibly fast from left to right. “They’re baboons” he realised, and climbed a tree to see better while I watched them through the binoculars. We returned to Gwen elated.

River life

Stone curlew ogling us with it’s big weird eye

Kingfisher in the bolon

Baboons through binoculars

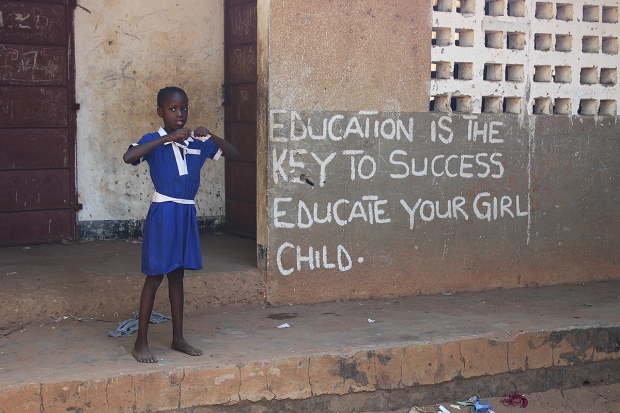

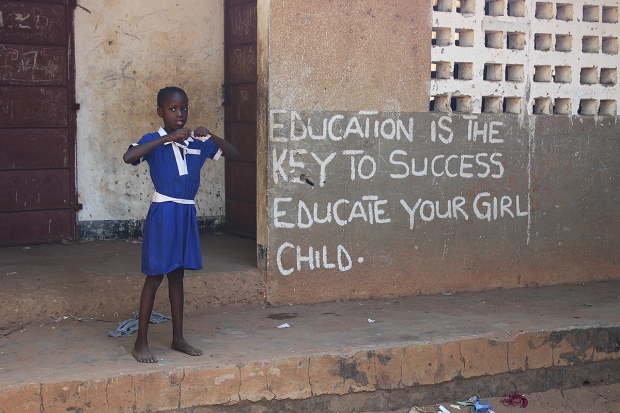

On the next day’s motor we got as far as Elephant Island (apparently there were elephants here a few hundred years ago), where we anchored overnight before visiting the village of Bambale on the mainland shore. It was a surprise to see the lush vibrant green of rice fields and earthy tracks of the village behind what seemed from the water to be a never ending world of mangrove. A kind young lad with only a little English walked with us through the village and taught us the few greetings in Mandinka that quickly became as essential to us as money and water. Until then we had only used the universal greeting of “Salam malekum”, but now we could ask after people’s families and spouses, reply to kindnesses from strangers and fulfill a cycle of friendliness and respect in new introductions. He drilled them in to us, questions and responses, as he took us to visit the local school, and came back with us afterwards to visit Gwen, whose solar panels and ukuleles impressed him greatly. Everywhere we go we exchange names with everyone we greet using the words he taught us, and my great regret is that I’ve forgotten his.

Bambale

Photos cannot do justice to the vivid green of this rice field

You find the kids in school, on the mud beach…

…or in a tree

We motored onward that afternoon and saw another yacht for the first time, reason enough to shout out a quick chat over the noise of the motor once we’d kicked it down to neutral. They were French, and they were heading to the school that we’d visited to play double bass to the children. We hadn’t brought a double bass and were a bit jealous. When the conversation stopped we powered on, still central in the river, far from each tantalising side where wildlife might hide. Rich had read somewhere that motoring up the Gambia can be boring at times and enjoyed loudly rebutting this dreadful inaccuracy – there was always something to see. “But it is a bit boring, isn’t it, I mean, it’s motoring and mangroves every day” I countered. He looked at me with genuine confusion and I shut up.

We anchored by another misnamed island “Sea Horse Island”, apparently so called because at some point the Portugese thought of hippos as horses of the sea. We prefer to spend the night out of sight of humanity, somewhere wild where the early evening and early morning fauna might be observed. Each night this means stopping and erecting the mosquito net by six and then preparing and eating dinner to the sound of a thousand birds as the day ends. Pigeons trill all day and there’s often a curlew scream or a distant toot, but at sunset the strangest calls join the mangrove chorus, with birds drilling, baying, yelping, chuckling and reversing their trucks. Some individual always has a repeating melody that gets stuck in your head. It’s never the same between locations. Monkeys sometimes join in, squawking and bitching and shaking the branches. Then as the light disappears these sounds fade and are replaced by the zithery vibrations of insects, bats and possibly frogs, their high pitched tones pulsating in overlapping morse code over the occasional splash of fish.

The next day, after all the joy of our trip so far, was inexplicably tense. Perhaps it had something to do with heat and dehydration or the fact we barely stopped motoring all day. We were pissy with each other and hyperemotional, and only had fun once we’d taken a quick break and explored some mangroves together. We caught sight of some red colobus monkeys, who looked and sounded as upset as we had been, and the large wet form of an otter as it scurried behind some roots. I also got to see my favourite bird so far, some sort of hornbill that looks like a miniature Zazu from the Lion King, whose up-down rollercoaster flight path includes soaring sections in which the wings are completely put away. They make flying look fun.

Just when you think you know what’s going on with the river three tubabs (white guys) drift past on stand up paddle boards.

They’re building a bridge at Yalitenda ferry crossing, which means that yachting like we have been doing may not be possible in a couple of years

This is what it’s replacing. The ferry doesn’t have much power and is quite scary/funny to watch.

Pied kingfisher. We see these everywhere and they’re incredible – they sometimes hover beautifully in mid air and are delightfully crap at hiding from boats.

Almost sunset from Sea Horse Island

By this point we had traveled well past the point of salinity where dolphins and pelicans live, but it was the next evening that we realised that the water around us was properly fresh. We’d been admiring the changing greenery lining the river, now including palms and large trees, and came around our last corner of the day to see the one and only hill we might be able to climb on our route, ready to glow red in the approaching sunset. We anchored as quickly as we could (dragging on our first attempt, of course, because we were in a rush) and threw up the mosquito nets before rowing ashore, exchanging greetings with every soul on and near the beach, and scrambling up. We were rewarded with breathtaking views of the world behind the high vegetation of the river shores and of irridescent birds in blues, greens and yellows. Just before dark we returned to Gwen for our usual sunset routine in which the one whose turn it is to cook cooks themselves as much as the food in our stifling galley while the lucky other stays outside where the heat is just about bearable (still sweating profusely, but with less of an urge to jump in the water with the crocodiles).

As we ate in the cockpit a high whine droned in to the boat from the land, getting louder and louder, squealing in with a batallion of mosquitos. As soon as one or two had hit the cockpit net there seemed to be a thousand. Soon we couldn’t stay in the breached outdoor space and retreated to the cooking pot that was indoors, but somehow mosquitos had infiltrated every cabin. We fought them off as best we could while trying to guess how they could have bypassed our defences, shoving plastic bags in to the anchor chain tube and taping up every vent, seal and space between inside and out. We spent an hour or two sweating, scratching our bites and drinking gin while leaping about with flip-flops and swatters, exterminating intruders, until we decided we’d done enough and erected the third line of defence, the bed net, climbed inside and finally found safety. Every night since has brought us a new, similar invasion but the masking tape and plastic bags seem to be holding out and they’re not getting in. The sound of them approaching each evening is more terrifying than that of any murderous mammal this country could produce. I’m looking forward to their numbers dropping back off at the salty end of the river.

Red hill of Kassang

“Oh what a pretty bit of river, I do hope it isn’t a hotbed of vicious insects”

Early yesterday morning we left the hill anchorage for Kuntaur (pffffft) where we indulged in the home comfort of some chips in a Dutch-owned restaurant overlooking our boat. We walked out of the village to see some mysterious 1,500 year old stone circles, and edged politely away from the guide after he linked them to symbolic theories that spanned navigation, astrology, numerology and language. His penny from 1960s Gambia was fascinating, but we could only take the New Age for so long and he was getting on to the illuminati when we finally made our escape. In the main-road town of Wassu we provisioned with the few veg for which we could communicate our desire to the women selling wares at the roadside, and met a man called Batch who drove us out of town for some diesel before taking us home. As I waited with him on the shore for Rich to return from the boat with his jerry can he told me that he’d spent time in Harlem in the 80s and worked as a cab driver in Detroit in the early 2000s. I’ve heard stories of adventure like this from a couple of men who look as part of the traditional village furniture as the red earth roads and the free range goats and chickens. It makes me think of my village back home – even in our little familiar heavens so many have wanderer’s hearts.

By the afternoon we’d had enough of the children who were banging on our boat, repeatedly asking our names and demanding presents we were not going to give them, and hoisted our anchor to slide past Baboon Islands, the national park where chimpanzees were relocated in the 60s and 70s. We had guidelines from Banjul telling us which routes around the islands were and were not allowed, and apart from the opening we were to travel mid channel at a great distance from the lush and secretive human-free habitats. We were not expecting to see much, particularly as the Harmattan seemed to have reappeared after a week’s absence. As we rounded the first and only island we were allowed to go behind, a ranger appeared beside us from nowhere in a dinghy and motioned for us to tie it on to Gwen. He told us what we already knew – that we could not go behind the other islands unless we were on an official tour boat, and that we could not approach them at any point. Unless… unless we wanted to take him with us, for a price, and he could point out some chimps, and then we would have to return to the centre of the channel. We leapt at this chance, and welcomed him on board.

What the ranger didn’t realise was that we were equally interested in seeing a hippo. It was a little while later that he casually pointed one out, quite close by (for a hippo) in the water off our port quarter. A whole head emerged from the water and splashed back in. We squealed and sighed, amazed. “You have not seen a hippo? There was one nearby when I met you” he smiled, and we raised eyebrows at each other. We needed to learn how to look for them, because obviously they were bloody everywhere.

Gwen traced the edge of the second island with all three of us staring in to the trees like shoppers at high street windows while Rich and I took it in turns to steer. The island, like much of the recent shoreline, had a great diversity of plant life including tall trees and palms whose lower fronds aged to grey, reminding me of Where The Wild Things Are. Finally we came to a few shore trees that were bowing and trembling with movement, rather like those in which we had previously spotted monkeys or large birds, and peering in we found whole families of chimpanzees eying us with stern curiosity or sleepy indifference from behind the leaves. After two such encounters our guide left us and we returned to the centre of the channel, from which we would spot a whole family of hippos once we’d got past the island. This time they were just a set of eyes, nostrils and ears, pointed towards us from their distant shallows.

Abandoned groundnut factories are a common sight on the river, which has seen much busier days

Every village we visit has astounding views from its little red roads. This one’s in Kuntaur

Wassu

Having a little bounce in a stone circle

Fly hunter

Fanny with her contemporaries at Kuntaur. I like the one with the school chairs in it.

Baboon Island inhabitants are, of course, not baboons.

Last night we anchored a little further on, and our dinner in the cockpit was accompanied by the gorgeous lowing of the hippopotomus. Hippos sound like the deepest voice you’ve ever heard laughing a slow chuckle. We couldn’t see them in the dark, but we heard them all around the boat, close by and continuing well after we’d gone inside to wash and gather around our tiny USB fan to read and play. It still feels joyously unbelievable that Gwen, a scruffy concrete boat from Millbrook, spent last night 150 miles up the Gambia surrounded by these shy and formidable pinky brown beasts.

Today we’ve spotted birds and baboons, distant hippos (now we have our eye in) and beach-prowling monkeys on and around the lush shores of the wide brown river on the first leg of a long return trip. Tonight we’re hot far beyond comfort and trapped in our boat by a legion of insects carrying a deadly disease, but there’s not a lot more happy we could be.

There are no hippo pictures because they’re either too far away, too briefly visible to find the camera, or just too amazing.